Jean Atkins nee Aitchison

Interviewed March 2010

Early life

Jean was born in Tunbridge Wells in 1924. She was intending to go to college after finishing school at Tunbridge Wells County Grammar but by the beginning of 1942 had realised that with the situation being what it was that she did not want to do this. ‘We were very aware of the war [in] Tunbridge Wells because we had the Battle of Britain going over our heads, we had the bombers going over to London’. Jean’s father had served in the Army in the First Word War, first in the cavalry in Gallipoli and then when he was commissioned, he was stationed to Northern Ireland. Her father met her mother after the war in Sussex, she had worked in her family’s village shop, driving the delivery van during the conflict. Sadly, Jean’s mother passed away when she was twelve. She and her little sister, in her words became much more ‘independent’ as a result.

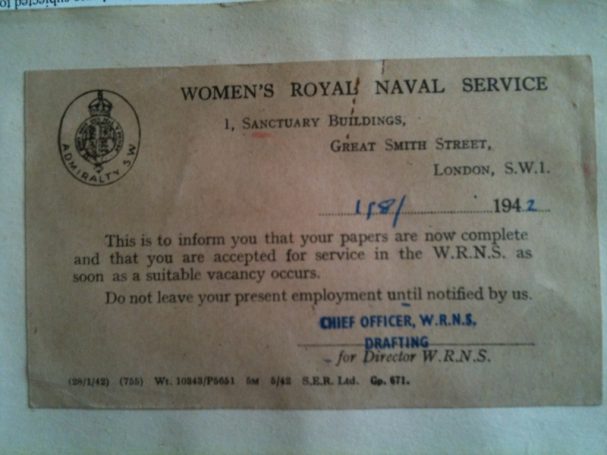

Joining up and initial training

Jean joined the service in 1942 when she finished school at 18 and served until May 1946. She learned there was a long waiting list to join but she got an interview at Chatham and received her calling up papers two weeks before finishing school – something she was not expecting to happen. She had thought there was no hope of her getting into the WRNS as she had no family connection to the Royal Navy (something she was asked at interview). What she did have that made her highly favourable, was a Higher School Certificate in maths. She did not have any opinion of the service before she joined but favoured the connection to the Navy because her father had instilled an interest in the sea and the Navy in Jean and her sister from an early age, as he was from Brighton. Her sister, Mary, would later join the WRNS in 1944 as a Topographical Wren and served in Ceylon during her two year’s of service.

Initial training for Jean was held at Mill Hill. The training venue had only just opened a few months before she joined with work men still finishing off parts of the building. She found her probationary time there ‘quite an eye-opener, I mean straight from school. First time I’d slept on a double bunk, though quite a few of the women in the dormitory were older than myself and more sophisticated. I’d never seen anyone pin their hair up or take so long to pin their hair up!’ She enjoyed her training and did not mind drill, ‘I enjoyed drill because I enjoyed games anyway and the lectures on Naval history and naval customs, it was quite interesting.’

Met Wren

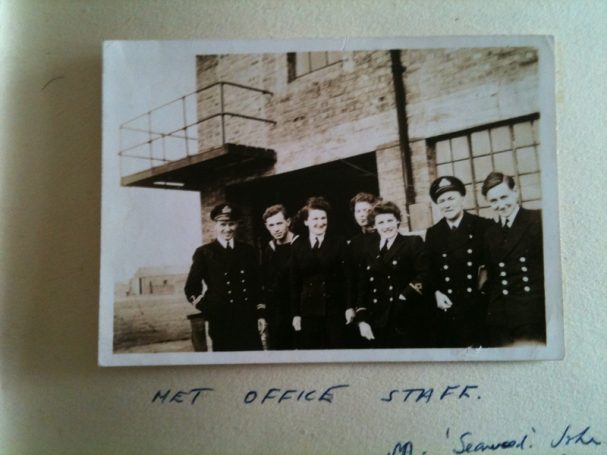

Jean applied to be a radio mechanic as that was on the list of possible roles at the time. When she got to Mill Hill, however, she was told that they didn’t need any radio mechanics and she was asked whether she wanted to become a Meteorological Wren. She was sent to HMS Merlin at Fleet Air Arm station in Donibristle after her initial training. She was trained on the job, something that was much more common in the earlier years of the war and with new categories (the Met Wren role only had only been started in 1942). Donibristle was a headquarters in Scotland for meteorology and had a pool of Met Wrens, which meant that if anyone went off sick or on leave on other bases they could be ‘loaned’ out. Jean got to sent to the Orkneys, Crail and Arbroath during her posting.

Being a Met Wren included plotting the weather on charts using information that came into the base via teleprinter. She would use mapping pens (red and blue) to indicate the level of visibility and temperature for their station. Other data collected would include cloud type and height, humidity, wind strength and direction, collecting data from an anemometer on the top of the building. This data would have to be updated and redrawn every three hours with the forecasters then joining up all the lines of pressure to get a whole picture of the weather. Once the weather reports had been completed, they would be sent to other stations to create a whole forecast for Britain, information that had been gathered from around 70 stations. Jean found her work ‘really interesting’.

Jean’s social life as a Wren was ‘very good’. She recalled ‘there was on every station there would be a cinema and something on every night and I remember that very well because I was brought up as part of a fairly strict non-conformist family should I or should I not go to the cinema! [laughs] But I soon got over my qualms about it [laughs]. But that’s the sort of thing that can you know, when you’re relatively young, I mean I was probably much younger for my age than an eighteen-year-old would be these days, but you have to think seriously about that, the way you were brought up you know?’ She also recalled Christmas times during the war that were fun and ‘very jolly’ with everyone able to have a bit of time off during the day and officers would serve the ratings in the mess.

Owing to her higher-level maths and physics she was able to go on and train as a forecaster. In Chapter 5 of ‘The WRNS in Wartime’ it is discussed how progressive the service was, focusing on the skills of the women, rather than their social background or who they knew. Jean was promoted to Leading Wren with this change in role and was restationed in June 1943. She trained at Dover serving in the casements below the cliff. The Wrens were billeted in the boy’s county school nearby and would be picked up by a Naval lorry in the morning, taken to the bottom of the hill where they would then walk up a side path to the castle. It had an entry via one of the balconies built into the cliff where the Wrens would be met by a sentry, and he let them through to then wend their way through the casements to where they worked. There was a small Met office there, which was different to the ground stations she had been used to. Being the year before D-Day, the focus had turned to understanding the weather of the English Channel, including swell forecasts, sea levels and fog. They had one Met Officer and he doubled up as flag lieutenant to the Admiral. Jean served alongside him and another Met Wren, her friend Millie.

In the build-up to D-Day, Jean remained stationed at Dover, which became busier and busier. In the months before the deployment, the base was put on restricted movement and no one was allowed to leave. One day Jean had gone to work and she was chatting to one of the sentries who said ‘“have a look at those barges in the harbour”, so I had a good look at them and I suddenly realised that their sides were flapping so they were mock barges [laughs] to make the Germans think that that was an invasion fleet building up in Dover harbour when of course they never went from Dover harbour’. Jean was certainly part of a key aspect of history here, having not known herself (as most of the members of the armed forces didn’t) where the deployment to France would come from.

She never felt scared during this time: ‘you see the thing is we were never really scared you know, we had tremendous confidence in the British forces and everything, yes I can’t remember feeling terribly intimidated. I must say it was a bit frightening when they started shelling because of the vibration, and of course the thing about shelling was that with a bombing raid you could hear the bombers coming so they could sound the sirens but the first shell that fell, nobody knew it was coming so unfortunately of course that would cause some casualties’.

Becoming an Officer

In August of 1944, Jean was sent to HMS Pembroke III, Stoke Poges, to train to be a WRNS Officer having been put forward by the Met officers. She was interviewed at the Admiralty to assess her suitability and then went for a three-week course at Pembroke to become a Third Officer (although in reality she was an ‘acting Third Officer’ as she wasn’t yet 21). Then finally she was sent to Greenwich to train as a Met Officer for three months. This role involved her creating the forecasts based on the information collated by the Met Wrens. Her first posting as a Met Officer was to HMS Landrail, Machrihanish. Here she served for eighteen months. She loved the work and although the location was isolated, she said there was lots of camaraderie. It was a big Fleet Air Arm station so had four Met Officer forecasters and around a dozen Met Wrens or Met ratings at any one time. When she was restationed here, she became a Third Officer officially, despite not being 21 yet – but no one questioned it.

Her final posting in 1946 was to HMS Caballa, a refresher station that allowed Wrens to receive training and courses in preparation to leave the service. Jean still wanted to continue to college, as was her plan before joining the Wrens, so she applied for a physics course. She left the service in May 1946. There weren’t the opportunities to go into meteorological work for women at that point, so instead she applied to join King’s College of Household and Social Science (which later would become part of King’s College London). She completed a course in home economics and then undertook a post graduate qualification in dietetics, becoming a dietician for a career. Her father had been critical of her completing a college course, as he thought there wasn’t much point if Jean was going to get married. ‘But of course since I got an ex-service grant, he wasn’t involved in the finances so it didn’t matter and I was able to make my own decisions’. This grant paid for all of her fees and most of her living expenses.

Post war

Jean met her husband in her thirties, having had a successful career as a dietician and teacher of dietetics. They had two children and after four years of being at home looking after them the lady who taught the dietetics course said that ‘being at home looking after kids was just sitting on your backside doing nothing!’ She was encouraged back into the workplace and worked part-time until retirement in ‘interesting roles’. Jean commented on the differences in lives of women post-war: ‘there seemed to be two different groups, there was some who married during the war and very soon after, and there was the group more like my friends, because none of us did that, who trained as something and worked for a bit and then got married’.

Jean said at the end of our interview that she felt ‘very proud’ that she had served in the WRNS, she also felt very grateful to have ‘had the opportunity to train for a very worthwhile career’. She thought it made women ‘better mixers’ and ‘less fussy’, by this she meant that women were less critical and more accepting of differences between people. Jean saw the war ‘as a good leveller’.

Photos shared from Jean

© Copyright Hannah Roberts 2025, © Copyright Hannah Roberts 2017 'The WRNS in Wartime', Bloomsbury

All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.