Clare Baines

Interviewed June 2010

Clare Baines' fascinating journey from the Women’s Land Army to the WRNS and beyond is a story of resilience, adaptation, and a thirst for experience. Her interview came about from talking to Evelyn's husband, Ivor, as both she and Evelyn served at the Nuremburg trials.

Early life and the Land Army

Born into a family that moved frequently, Clare found herself in London during her formative years. As war loomed in 1939, a chance encounter with a “bossy” lady who lived in one of the flats in the building her family were living in led to a pivotal decision: Clare would join the Women’s Land Army. At 17 years old, she was thrust into the hard labour of farm work, planting fields of cabbages, battling relentless weeds, and hauling water with horse-drawn carts.

Despite the physical toll, Clare embraced the experience of the Land Army, later reflecting on its impact: the challenges and independence of farm life shaped her worldview more profoundly than a traditional education might have. She said of this time: “I’ve got a theory that what you do between 18 and 21, marks you for life. You’ve just got off on your own, I should have been at Oxford at the time, and I wasn’t, but, I feel I owe a lot more to those 3 years on the Land Army than I would’ve, those 3 years at Oxford.” She often joked about her experiences, once quipping that if she’d been paid a proper wage for her work with cabbages, they would have been too expensive for anyone to buy! Clare cherished the camaraderie and new perspectives she gained during these formative years.

Transition to the WRNS

In 1943, Clare’s life took another turn when she joined the WRNS. Family concerns about her well-being, combined with a recovery period after surgery, prompted the shift. Inspired by her older sister, who was already serving as a linguist in the Wrens, Clare embarked on this new chapter as a Special Duties Linguist. This role was in demand by 1943 with increased shipping and air activity in the channel.

She quickly adapted to the rigorous training, learning to tune into enemy frequencies and decipher German Morse code. She later described the meticulous training process, explaining how her performance in speed and accuracy tests determined assignments. Clare’s humour shone through in her anecdotes about strict uniform regulations—she recounted how one clever colleague kept hairpins on hand to ensure her hairstyle met inspection standards. She also discussed how silly she thought some of the rules were:

“And they had a thing about, us not speaking to the sailors, which was idiotic…And being late because you weren’t early and that sort of thing!”

I asked her why they were not allowed to speak to sailors:

“I’ve no idea. But they worked in another house and for some reason or other we swapped over at break time. And they walked through the garden to our house, and we walked through the garden to theirs. We had to go the other side of the rose bushes. I’ve no idea why! That’s a very odd idea. I mean, there must have been some antediluvian people there!”

Stationed at Gallstone and later Cornwall, Clare’s duties included monitoring Luftwaffe communications and intercepting critical information for Bletchley Park.

“I think after the invasion started there were all sorts of things. You got, mostly the Air Force, you got interception of bombers who, you got the fighters, sometimes you got the fighters being brought back with one engine gone and we got very excited to see whether they were going to land or not.”

Long night watches and intense concentration marked her work, but Clare’s resilience and ability to find humour in challenges kept her motivated.

Nuremberg Trials

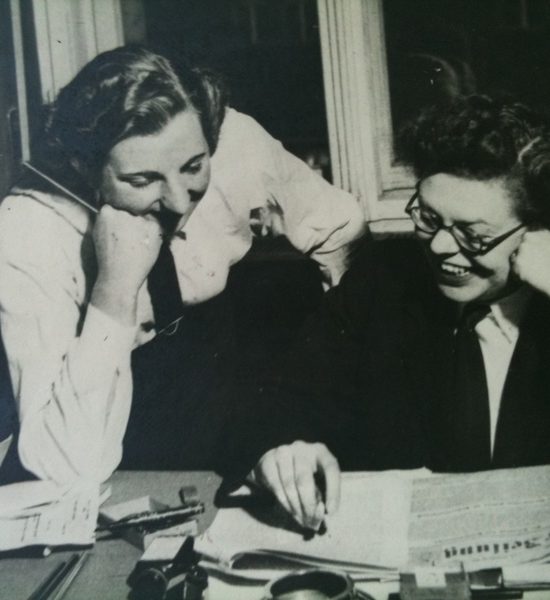

At the end of the war, Clare’s skills took her to Nuremberg, where she contributed to the historic trials of Nazi war criminals. Her journey to Germany came through her assignment as a linguist with the Wrens, during which she was seconded to work alongside Allied forces. She travelled to Nuremberg in October 1945, joining a group of translators and interpreters housed separately from the main British contingent. This setup, organised by the Americans, provided unique living arrangements and an environment where Clare encountered people from various nationalities and backgrounds. It was also where she met Evelyn Glazier.

In Nuremberg, Clare played a pivotal role as a linguist, translating key documents and ensuring they were available in English, French, and Russian. She described the exhaustive process: staying up all night to complete translations for court sessions the next day and witnessing firsthand the intricate dynamics of the trials. Clare remarked that while the work was fascinating, extended time in the courtroom could be incredibly monotonous.

Reflecting on the trials, Clare emphasized the importance of documentation in preserving history. She noted the challenges of trying defeated adversaries but valued the transcripts as a permanent record that future generations could consult. Clare’s sharp wit was evident in her account of realizing that one of her German housekeepers in Nuremberg had previously worked in the Luftwaffe, tracking Allied bombers. “The chances are I’ve listened to you!” Clare recalled, though she kept this observation to herself.

Post-war reflections

Clare’s post-war years were as varied as her wartime service. She finally attended Oxford at the age of 24 but found the experience lacked the novelty and independence of her earlier roles, finding it “puerile”. She later pursued positions as a librarian and translator and even managed a physiology department in Germany for six months. Clare credited her wartime service with expanding her horizons and providing opportunities she might not have otherwise encountered.

Ever candid, Clare often reflected on the broader impact of women’s wartime contributions. She believed the Wrens and Land Army gave many women, especially those from rural backgrounds, a chance to experience new environments and gain independence. “It gave a tremendous fillip to all sorts of people who wouldn’t have had the chance otherwise,” she observed. However, she said although “it was very good experience, for getting to know other people and other things, that you wouldn’t have come across otherwise. But if it takes war to do it, we can do without that!” Clare’s humorous take on reunions underscored her independent spirit: she avoided them, joking that “the sort of people who go to reunions are the ones you least want to see again!”

Legacy of a life well-lived

Clare Baines’s story is one of adaptability and curiosity. From the farms of the Land Army to the radios of the Wrens and the historic halls of Nuremberg, her life exemplifies the resilience and resourcefulness of women during wartime. Clare’s reflections, filled with humour and insight, remind us of the transformative power of stepping outside one’s comfort zone—and the enduring impact of service during extraordinary times.

© Copyright Hannah Roberts 2025, © Copyright Hannah Roberts 2017 'The WRNS in Wartime', Bloomsbury

All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.